-

Deinfluencing: Etat Libre d’Orange (and Guerlain takes some strays)

I started seeing ads for Etat Libre d’Orange, a French perfume house, sometime last year. Before I left Facebook, it seemed like I was seeing at least one ad every time I scrolled. The ads worked because I got lured into buying a decant of You or Someone Like You from in the early days of my hyperfixation on fragrance. In part it was the notes—I’ve been into green/fresh scents—but it was also the proximity to the title of the Matchbox 20 album Yourself or Someone Like You, which I listened to about everyday in eighth grade.1

When I tried it, I fell in love. There’s this initial mojito-like blast in the opening that fades into an old-lady-ish rose. I hadn’t smelled anything like it before and wanted a full bottle. The price on the regular website, $110 for 50mL/$170 for 100mL, was a bit more than I wanted to pay2, so I started searching for bargains. I’d seen it mentioned on Reddit that TJ Maxx sometimes gets ELDO at a discount.3 I didn’t find You or Someone Like You. I did, however, find another perfume of theirs: Story of Your Life. You may see a trend here, but the name of the perfume reminded me of Ted Chiang’s novella4, so that caught my attention. A scan of Parfumo revealed a brioche note—who wouldn’t want to smell like brioche? But the copy on the ELDO website drew me up short:

The more I learn about generative AI, the more I am against expanding its use beyond limited practical applications in medicine and other sciences. When I see no justification for a company’s use of AI, I see no justification in them getting my money, particularly for a luxury product like perfume. I am admittedly biased, having briefly worked for a generative AI company before becoming a writing instructor, but the environmental and labor issues5 involved should be a concern to anyone. Taking a closer look at the cocarde, where ELDO “played with” an AI, there’s nothing about the design that’s particularly revelatory or interesting.

Heart shapes to represent love.

It looks like a smudgy thumbprint.

While looking for a substitute for You or Someone Like You, since I won’t be buying from ELDO, I saw Guerlain’s Aqua Allegoria Rosa Verde or Herba Fresca have some similarities in green notes. But in perusing the website, repeated phrases like “a powerful symbol” and “an invitation” triggered my spidey senses, and it didn’t take long to find out how they are embracing AI as well. Known for their iconic bee bottle, which was first created for Empress Eugenie, Guerlain used AI to reimagine the bottle in its various iterations from 1853 to 2193. They created a video but the explanations of their reasoning and process are more interesting because, frankly, the “art” looks like shit.

You might ask yourself: who were the artists that the references “were borrowed from,” or where they see their product fitting into the solar punk movement? The composition of perfumes is both art and science. A nose undergoes many years of training in order to work for major houses, sometimes completing advanced studies in chemistry prior to perfumery school. It seems akin to artists working as apprentices under a master to learn their craft, requiring perhaps some innate skill in sense of smell but more importantly—hard work. I would assume that fellow artists would respect human labor and creativity in other fields and avoid generative AI. And yet, beyond just using it as a sloppy shortcut for design to promote their products, some perfumers have embraced AI in the creation of perfumes. Renowned perfumery school Givaudan touts its program Carto’s ability to create instant samples using “the best possible formula” and says the program “makes the process more efficient and enjoyable.” Carto and similar programs pose an opportunity to reduce material waste and labor hours and, in the best of all possible worlds, would make life easier for the worker. I doubt it will be used that way. Gareth Watkins, writing on the links between AI and fascism, has pointed out:

That even the best AI models are not fit to be used in any professional context is largely irrelevant. The selling point is that their users don’t have to pay (and, more importantly, interact with) a person who is felt to be beneath them, but upon whose technical skills they’d be forced to depend…For its right wing adherents, the absence of humans is a feature, not a bug, of AI art.

Once the noses have trained these programs to be “good enough” companies will look for ways to pay workers less or replace them altogether. The potential expendability of labor is why so many companies have bet big on a technology that many consumers simply do not want.

Carto was used to create ELDO’s She Was an Anomaly in 2019, and the description from their website emphasizes how the company positions itself as an outsider—there is an ironic element here, as it suggests, but the company itself does not seem to understand where the irony originates:

Another small, icky detail: The name of this perfume was taken from Nina Simone speaking about her mother.

If Daniela Andrier couldn’t use her own human brain to come up with something like this, I’m concerned. These are perfectly normal notes. These self-described eccentrics and deviants share DNA with other industry disruptors. Etienne de Swardt’s South African origins and obsession with being seen as an edgelord naturally call to mind Elon Musk. Etat Libre d’Orange, or the Orange Free State, was an independent Boer republic that ceased to exist following the end of the Second Boer War in 1902. De Swardt chose to honor his birthplace when naming the company, describing it as “a land of staggeringly rough beauty and color and unforgettable smells, a nation of contrasts, strong feelings, and mixed emotions. A rainbow mosaic of people and cultures and it was independent.” Now, I have just a soupçon of knowledge of South African history, but I think anyone passingly familiar with the horrors of colonialism and apartheid might question the romantic image he creates.

Following the end of the Orange Free State, the newly-formed Union of South Africa enacted one of its first major segregation laws in 1913. The Native Lands Act mostly banned the sale or lease of land to Black people outside of limited reservations, helping pave the way for later apartheid laws. Sol Plaatje, an African writer and politician born in the Orange Free State—who later was a founding member of the African National Congress—wrote Native Life in South Africa in 1916 as response to the law and highlighted how the act was inspired by extant codes in Orange Free State:In this connexion, the realization of the prophecy of an old Basuto became increasingly believable to us. It was to this effect, namely: “That the Imperial Government, after conquering the Boers, handed back to them their old Republics…That the Boers…will make a law declaring it a crime for a Native to live in South Africa, unless he is a servant in the employ of a Boer, and that from this it will be just one step to complete slavery.” This is being realized, for to-day we have, extended throughout the Union of South Africa, a “Free” State law which makes it illegal for Natives to live on farms except as servants in the employ of Europeans…He can only live in town as a servant in the employ of a European. And if the followers of General Hertzog are permitted to dragoon the Union Government into enforcing “Free” State ideals against the Natives of the Union, as they have successfully done under the Natives’ Land Act, it will only be a matter of time before we have a Natives’ Urban Act enforced throughout South Africa. Then we will have the banner of slavery fully unfurled (of course, under another name) throughout the length and breadth of the land.

Following the enactment of the legislation, white farmers began to expel Black farmers from their land and police in the former Orange Free State militantly enforced pass laws to regulate movement, employment, and residency. Obtaining a pass cost money that many Black people could not afford, particularly once their property was seized, but those found without passes were subject to violence, fines, and imprisonment. As de Swardt said in an interview with Fragrantica6, “The Boers wanted to reinvent rules their own way.”

Positioning himself and his company as outsiders is also interesting given de Swardt’s background as an executive for LVMH, a conglomerate that specializes in luxury goods. He did for their companies what he does for ELDO: he provides ideas for perfumes and marketing and has other people create them, as he is not a nose. His first independent venture was a perfume for dogs, an idea which raised $12 million but was “ahead of its time” and not much of a success. De Swardt launched ELDO in 2006. Among the first fragrance releases was Secretions Magnifiques, created by Antoine Lie, which has accords of blood, sweat, semen, and saliva. I appreciate an avant-garde approach and pushing the boundaries of what we think fragrance can be. But other details, like choosing 69 Rue des Archives as the address for their flagship boutique, or having perfumes called “Philippine Houseboy” and “Don’t Get Me Wrong Baby, I Don’t Swallow,” suggests that ELDO is not so much avant-garde as puerile.7 While they do demonstrate more restraint in their deployment of AI than Guerlain’s slop, ELDO’s use of the technology is a handy red flag for a consumer wanting to avoid creeping fascism.

- I hadn’t heard of the book it’s actually named after. You or Someone Like You is by Chandler Burr, who is more known for his perfume criticism than his fiction. His book The Perfect Scent: A Year Inside the Perfume Industry in Paris and New York is on my TBR though because it follows the creation of Un Jardin sur le Nil by Hermès. ↩︎

- This is not the most fiscally responsible hobby I could have chosen. ↩︎

- For those also looking for bargains, the chain sometimes gets DS & Durga and Vilhelm Parfumerie. Costco online is always worth checking, too. ↩︎

- I have better taste in books than in music. ↩︎

- On the subject, I’m looking forward to reading Karen Hao’s Empire of AI, which investigates these concerns in the context of OpenAI/ChatGPT. ↩︎

- I am not linking to Fragrantica because unpacking their batshit views is a whole other blog post. Use Parfumo to look up your notes. They’re more accurate anyway. ↩︎

- Since renamed “Le Fils de Dieu du Riz et des Agrumes” and “Yes I Do” respectively, so perhaps the appeal of being edgy has worn off in the face of investors. The scents themselves sound fairly conventional. ↩︎

-

Nature hath given her no knees to bend

I have this one story, maybe my favorite story but definitely my weirdest story, that I haven’t quite figured out. It’s got all my favorite things: early cinema history, anthropomorphic animals, grocery stores, prehistoric art, surly girl scouts, a last line. I just don’t know how to stitch it all together, so it’s been sitting over a year now, gathering dust. There’s so many things I’ve just barely drafted and then dropped because I felt like I didn’t yet have the tools to write it. But yesterday, seeking out something short to read by the Christmas tree before I have to toss it into the fire pit, I happened to pick up The Only Harmless Great Thing by Brooke Bolander, a used bookstore impulse buy so small I forgot to feel guilty about it languishing in my TBR pile. I read it in one sitting and now I’m sketching out how I might pull off that old story as a novella.

I struggle with a lack of patience as a writer (and as a human being). I want to be good at everything right away, I want to get to the parts that interest me quickly, and I want a reader to keep up without me having to explain. I was a poet before I was a fiction writer, which lends my writing imagery but also obtuseness. I’m all vibes, little plot. It has made transitioning from writing short stories to writing a novel difficult. I’ve been eyeing the novella as a stepping stone between the two. The Only Harmless Great Thing touches on some of my 2AM Wikipedia obsessions—the glowing cat and atomic priesthood proposals for long-term nuclear waste messaging, elephant death rituals, Radium Girls—and some of the big concerns in my own writing: worker exploitation, animal and human relationships, the immensity of time and the rhymes of history. Bolander’s novella both encouraged me, in that it is possible to create something beautiful and meaningful that packs so much in a tight space, and dismayed me, in that way I sometimes feel after reading something I wish I had written.

In this book, Bolander splits the story like an atom, letting it echo across history from wooly mammoth cosmology to a future where humans may not be the only sentient creatures we have to warn about our current shortsightedness because 10,000 years is on the shorter side of just how long nuclear waste might be harmful. The multiple POVs twist together across time and space. It might be labeled a mosaic, with discrete pieces placed side by side to tell a single story, but this book made me think about the limitations of labeling a work a mosaic narrative. Would it be more useful, for my own understanding, to think about the ecology of a story? Not in the sense of a story being about nature, but in the sense that each piece is a living organism and by necessity exists in connection to all other pieces. In reading The Only Harmless Great Thing, the intense limitations of human perspective are stark. Our cognition and our lifespans only allow us to see so far, particularly if all we want is a bird’s-eye view of the picture on the ground. To return to my impatience, I have been looking for an easy way to see a big picture of a story from above. What this book made me consider is that perhaps I need to look at the pieces of my problem-child story from inside, to see where the rhizomes are creeping under the surface connecting my obsessions at a subconscious level.

-

Dietary Dogwhistles

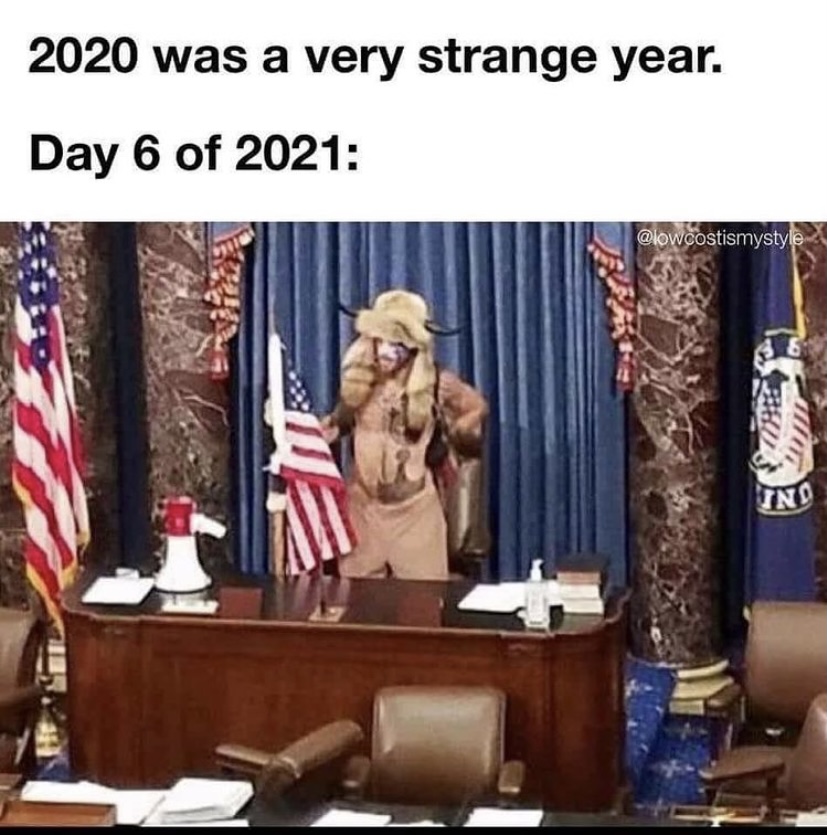

Following the assault on the U.S. Capitol on January 6th, one of the most indelible figures was Jake Angeli, the QAnon Shaman. While The Handmaid’s Tale and *gestures wildly at everything else* has been preparing me for a theocracy, I wasn’t quite expecting it to be Wotanist. After roaming the halls of Congress in face paint and furs and returning home to Arizona, Angeli has since been arrested and held on federal misdemeanor charges. He made the news once more after his public defender told the judge Angeli has not eaten since being taken into custody because he is on a restrictive diet consisting exclusively of organic foods.

Angeli’s mother told reporters “he gets very sick if he doesn’t eat organic food – literally will get physically sick.” While the government has previously ignored dietary requests due to religious or health reasons, most notoriously feeding Muslim detainees pork, U.S. Marshals indicated that they would follow the judge’s order to provide Angeli with organic food. I’m no longer surprised at the special treatment white supremacists get from our government, but I was left wondering: what does a Q shaman eat?

What we talk about when we talk about Q shamans Angeli’s Q Shaman personality seems to stem from the Neoshamanism movement, a syncretic, culturally appropriative system. Michael Harner, who wrote The Way of the Shaman, promoted this “core shamanism” to white audiences as an umbrella for practices ranging from healing, making psychic journeys to other worlds, and interacting with spirits, lifting rituals from Indigenous peoples in the Americas, Siberia, and elsewhere. Frederick Kunkle, in The Washington Post, summarizes Angeli’s beliefs:

Chansley [Angeli’s legal name] said he had spent much of his life around Phoenix, following a spiritual path that led him from Catholicism to a mix of pagan and New Age-like religious beliefs. His shaman’s clothing reflected that, he said. The fur is that of a coyote, an animal that some Native American traditions have long regarded as a trickster.

‘That’s why I wear the skin…because you cannot pull the wool over the eyes of an Angeli,” he said.

He is also heavily tattooed with Nordic insignia that Rolling Stone reported as having been adopted by far-right white nationalists.

QAnon views are positioned as a glimpse beyond the veil, pulling the wool away from the eyes to reveal the secret war that Trump is fighting against Satan-worshipping, cannibalistic, pedophiles who hold positions of power in government, media, and business. Adherents look for cryptic messages in digital media and await an apocalyptic “Storm” when this cabal will be brought to justice. A Q Shaman, as such, could be said to deliver messages from this other world.

Curiously enough, the shamanism practiced on the steppes, from where the term originally derives, historically has its roots in resistance to colonialism. Chris Gosden in Magic: A History, writes:

For the groups we now see as the indigenous peoples of the grassland Steppe, forest and tundra, the last two millennia have witnessed incursions of a great variety of polities, who have taken land, extracted resources and pursued goals of their own, often through conquest and subjugation…Shamanism arose from a repurposing of earlier belief systems, which came into being around a politics of resistance to unified groups, such as the Uighurs, and it has developed in this vein ever since…Shamans were group spiritual trouble-shooters, tasked with attempting to resolve issues facing the group, which might manifest themselves in everyday reality, but always had a root in the spirit world. As the troubles of colonialism proliferated, so too did the shamans (181-2).

It adds an extra layer of absurdity (and disgust) then, seeing a man who has clearly benefited from white settler colonialism take on the mantle of shaman in his actions to oppress and disenfranchise others.

Those of us who have lost loved ones to the Q cult or Trumpism know that a lot of people genuinely believe these conspiracy theories, and I’m not going to debate the sincerity of Angeli’s beliefs here. Legally, in the United States, reasonable accommodations must be made for a person’s religious practices. So then, if it’s not just a ploy to perhaps get better food (though I don’t deny that may be part of it), what does Angeli’s request for organic food tell us about his beliefs?

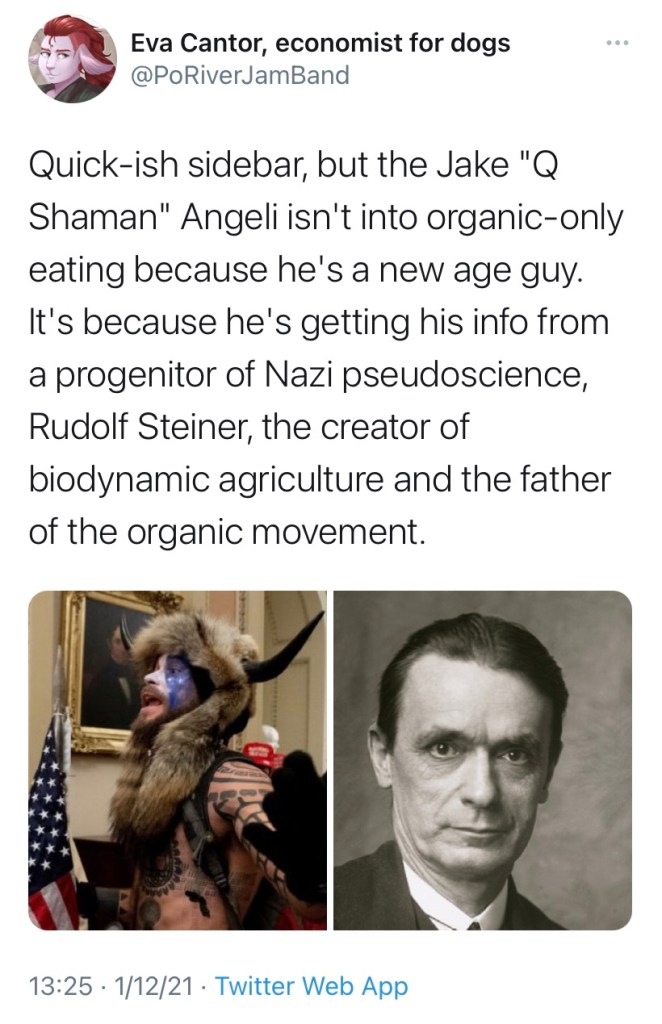

Nazis at the Farmers Market The organic food movement is often seen as elitist, led by cheerleaders like Michael Pollan and Alice Waters, criticized for advocating a diet few can afford which may not even lead to better health outcomes and which centers white culinary traditions. In recent years, former darlings of the movement like Joel Salatin and Baker Creek Heirloom Seeds have revealed that the libertarian streak among some organic farmers is in many cases built on a foundation of white supremacy. While folks like Anderson Cooper might portray the rioters at the Capitol as uncultured buffoons on their way to a celebratory dinner at the Olive Garden, white supremacy and organic agriculture have more links than one might think. Eva Cantor, an organizer and economist, pointed this out on Twitter in a thread that’s gone viral in food circles.

Before this, I’d only ever heard biodynamic used interchangeably with organic, occasionally noticing it on some labels at the grocery store. Taking a deeper dive, I found it has practices more associated with sympathetic magic than science, such as burying a cow horn full of manure or quartz or preparing teas with ingredients like horsetail or yarrow for the compost pile, as if treating soil with homeopathic medicine.

Now, I come from people who plant by the signs, so that doesn’t sound too incredibly strange. But Steiner’s thoughts on Atlantis and race evolution do more than complicate matters, as his modern Waldorf supporters would say, but rather provide more evidence that a fixation on clean eating and clean bodies more often than not is rooted in white supremacy and that sometimes environmentalism takes on an ecofascist bent.

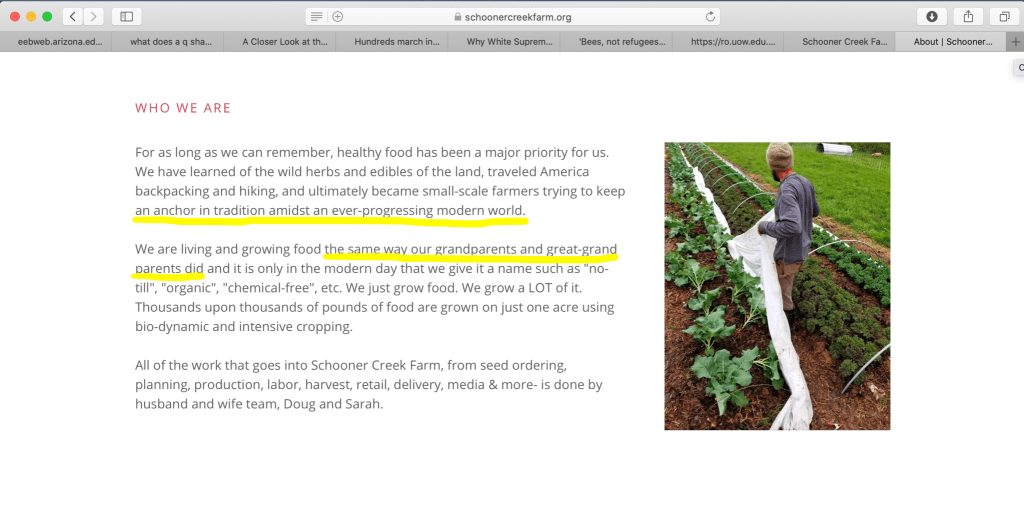

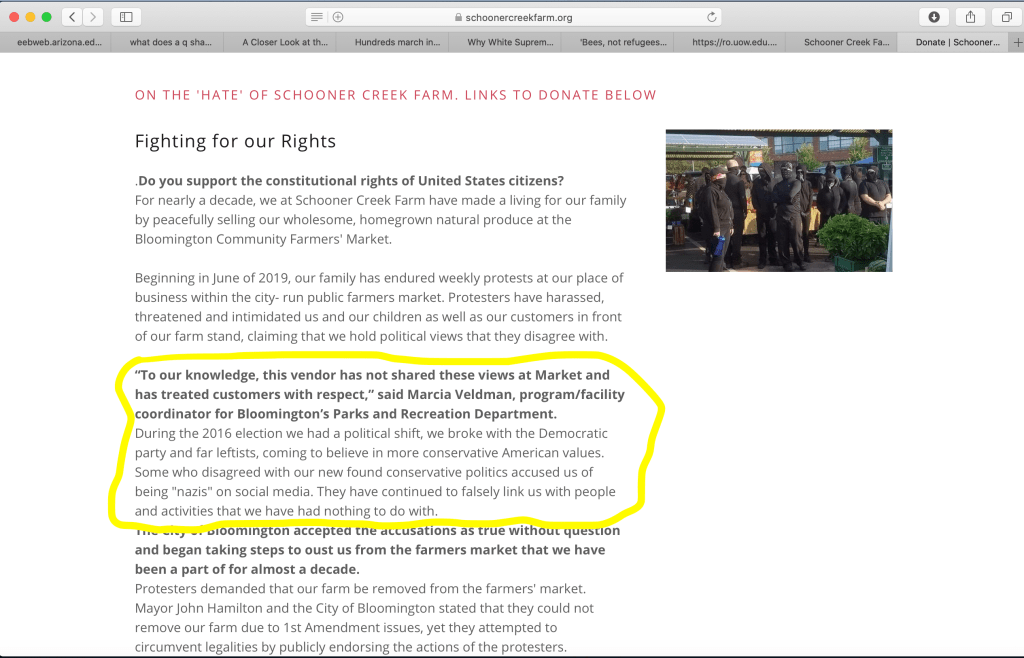

When I briefly worked at a farmers market, there was a particular farm we always hoped to avoid being near. The farmers were unpleasant, often pushing away the merchandise tables of neighboring vendors if they felt they were too close and never greeting others. I didn’t think much of it until one morning, with no preamble, one of those farmers asked my coworker, “are you a Jew?” She chose to ignore him and went about her day, but we found out later that such interactions with them weren’t that uncommon. Apparently they’re not uncommon at other farmers markets either. In 2019, in Indiana (Mike Pence’s home state), the Bloomington Community Farmers Market was briefly suspended when a vendor, Schooner Creek Farm, was revealed to have ties with a white supremacist group. Activists came to the market to stand in front of the stall and inform customers, which attracted the attention of an armed militia. The mayor closed the market for two weeks due to safety concerns, but later reopened. Schooner Creek was allowed to stay (as were the racists at my own farmers market), and some vendors and customers chose to leave due to the lack of response. On Schooner Creek’s website, responding to the protests and painting their racism as a First Amendment issue, they say, “We just want to be able to continue farming in peace and providing wholesome food to our community.” But if we’re reading between the lines, we can pick out some phrases that dog whistle:

And then some that just whistle:

Far from enclaves for gentle hippies, farmers markets can be a comfortable gathering place for white supremacists seeking a return to their imagined Eden, who are well-accustomed to listening at different frequencies. What’s worse is that these individuals and farmers are protected, not just by armed militias, but also more perniciously by the unwillingness of other white people to fully reckon with racism in their communities and race-based discrimination from the USDA and banks that keep Black people and other people of color out of farming. While Angeli sounds a bit ridiculous in the Washington Post, saying “when you watch television, when you listen to the radio, there are very specific frequencies that are inaudible that actually affect the brain waves,” it’s not an unreasonable analogy for the impact centuries of white supremacy and our current media diet has on our consciousness.

Blood and soil, milk and soy If seeking portents for what’s happening currently, we can look back to the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville in 2017. Watching footage of the white supremacist protesters there was the first time I (and I assume many others) had heard the phrase “Blood and Soil.” The use of this phrase is based in Nazi ideology, which praised rural farmers with long family ties to Germany and sought to instill a sense of national pride in these populations. Nazis mixed their metaphors in extending this, referring to Jews as both rootless and weeds. This ideology manifested in Lebensraum, where Germany sought to expand its territory into Central and Eastern Europe, allowing for more control over its food supply through farmland and thus preventing being starved out by British blockades.

The food ecology that Angeli comes from has had two prominent concerns emerge in the past couple of years: milk and soy. While the rhetoric surrounding them occupies opposite ends of the spectrum, with one a source of praise and another an insult, at the core of these messages is the same concern over pure land and bodies.

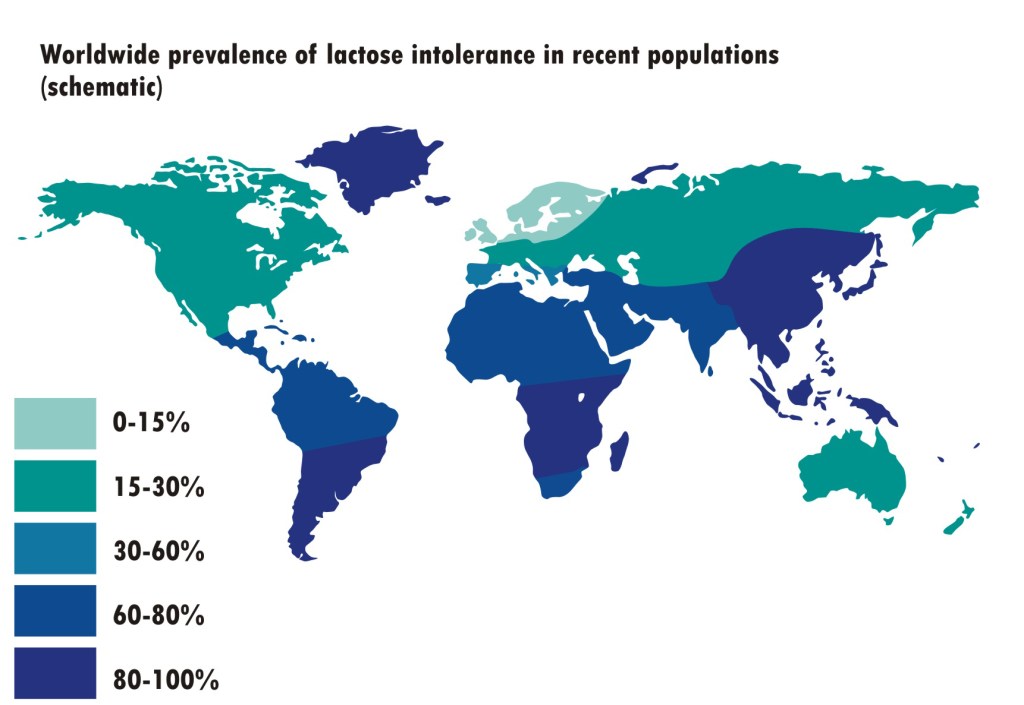

In 2017, Richard Spencer, the neo-Nazi with an eminently punchable face who coined the term “alt-right”, put a milk emoji in his Twitter handle. The majority of adults worldwide (about 65%) cannot properly digest milk. The highest rates of lactase persistence are in northern Europe and Scandinavia. White supremacists seeking evidence of their superiority seized on this fact, and have flooded social media with images of tall glasses or gallons of milk, bragging about their ability to consume it in comfort. For them, I’m sure it’s a delightful coincidence that their beverage of choice is white.

Get Out, Jordan Peele, 2017.

Far from an odd modern curiosity, milk has been associated with white supremacy in the United States for at least 100 years. In the 1920s, the National Dairy Council wrote, “the people who have achieved, who have become large, strong, vigorous people…who are progressive in science and every activity of the human intellect are the people who have used liberal amounts of milk and its products.” In the 1930s, History of Agriculture of the State of New York stated, “of all races, the Aryans seem to have been the heaviest drinkers of milk and the greatest users of butter and cheese, a fact that may in part account for the quick and high development of this division of human beings.” More recently, in 2015, The Economist published an article that echoed this racism, arguing that consuming milk helped Europe conquer the world. This dietary racism is codified in the Farm Bill, which places a heavy emphasis on dairy products in the WIC program and creates barriers to milk alternatives, even though people of color experience higher rates of food insecurity and are more likely to be lactose intolerant.

Around the time #milktwitter emerged, so did a new insult: soy boy. Some white supremacists posit that the high levels of phytoestrogens in soy reduce testosterone and sperm count. They believe there is a left-wing conspiracy to “create an army of soy boys from birth” through the use of soy baby formulas. While there is not a scientific consensus over the effects of soy on health, the rampant misogyny in white supremacist circles has seized on its connection to estrogen as a threat to the robust Aryan body, and thus it has become a way to insult the masculinity of leftists or anti-fascists. Soy’s popularity in East Asia, among populations that are frequently lactose intolerant, has led to the repackaging of the colonial derision of the “effeminate rice eater” in the 19th century.

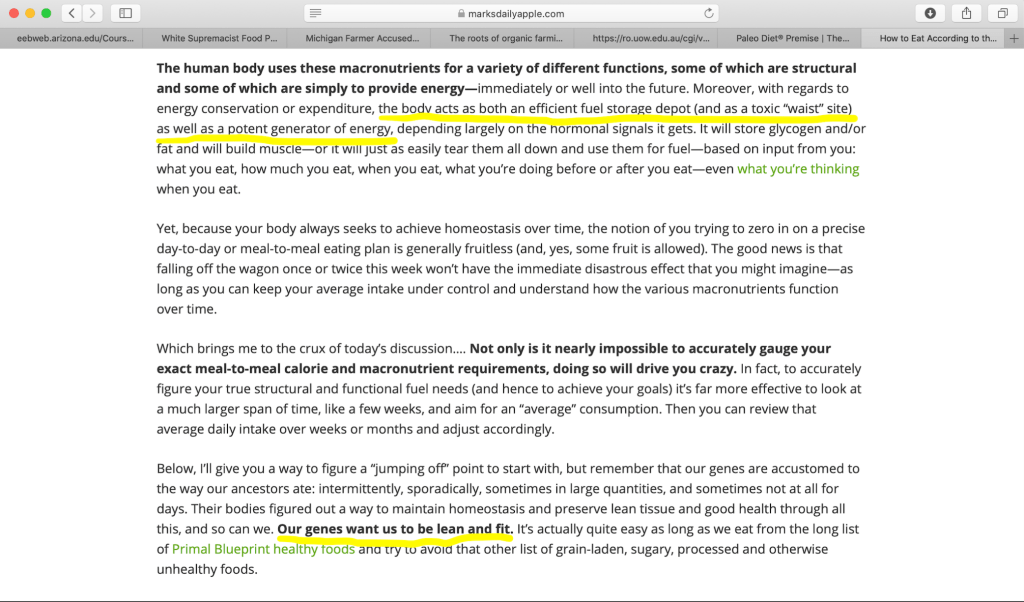

In other circles where racists proliferate, like CrossFit, this disparagement of a plant-based diet plays out in the popularity of paleo-type diets that emphasize the consumption of meat and “right” plants. While not overtly white supremacist, we can look at copy from Mark’s Daily Apple and see a preoccupation with genetics and the productivity of the body that is uncomfortably close to it:

To Eat and To Be For Angeli and other white supremacists, their concerns about food seem to turn an old adage on its head: you eat what you are. What they desire to be is pure and separate, and their thoughts about appropriate diet reflect that. While this is the food ecology that Angeli’s dietary hangups emerge from, it’s important to note that it’s a milieu most of us swim in without noticing. Especially in January, a large portion of media and thus psychological space is preoccupied with weight loss, wellness, and clean eating, and that messaging is often subtly reinforcing white supremacy. When you, especially if you are a white person, do a Whole30 challenge or a juice cleanse, you may assert that you are doing it for health. I ask you to stop and consider: what do you believe is healthy, and why do you believe that? Who are the people giving you this information? What type of body are you trying to create, and why do you want to change?

-

East Boone Coffee Shop

Over the past couple of years, Hatchet Coffee has become an essential stop for me whenever I visit my family in the mountains of North Carolina. I grew up in Watauga County and didn’t really become a coffee drinker until I moved to the Triangle and discovered beans that weren’t dark roasted or artificially flavored. On visits home, I’d resigned myself to K cups until I tried Hatchet for the first time.

I was surprised to find Hatchet in a small business park off Bamboo Road. I lived the first five years of my life in the trailer park that’s now just a couple minutes’ walk from the shop. Hatchet’s initial location was tucked into a space shared with Center 45, a climbing gym. Both businesses have since expanded in the same area. There’s also now a tattoo studio and, prior to COVID, regular food trucks and pop-up markets. Their neighbors also include a rock quarry, homeless shelter, food pantry, and, until last summer, a methadone clinic. When I lived in Boone, that road had been mostly a cut through for drivers looking to avoid town traffic by going over Wilson’s Ridge.

I’m not unaccustomed to change in my hometown. Since moving away, each visit I seem to notice a new student apartment complex or chain restaurant that’s sprung up in the last ten years. There’s even a Starbucks, which for years had divided residents who either desperately wanted it or who believed it would destroy what little local coffee we had in Espresso News or Higher Grounds. Living and working in Durham though taught me that a coffee shop or a brewery in a neighborhood once labeled sketchy usually meant that the folks who’d been living there were about to see a lot of new neighbors and higher rents or taxes. It turns out this area has both a coffee shop and a brewery and a new name: East Boone. (Check out a map of East Boone here)

I first noticed this name while checking out the merchandise table at Hatchet. On the back of one of their mugs, the location was listed as East Boone. A quick check of their Instagram revealed #eastboone in frequent use. I asked the barista about it and she said that Hatchet, along with some other businesses, had started using it to market their neighborhood. After having a laugh about it with some family, I started digging around and found East Boone’s earliest mentions appear in the spring of 2018.

An article in the Watauga Democrat reporting on the relocation of Booneshine Brewing Company to the Industrial Park area quotes co-owner Tim Herdklotz as saying “‘There are some exciting things going on in this side of town. Hatchet Coffee, Center 45, are happening in this area, so we’ve kind of partnered with those guys and started to call this part of town ‘East Boone.’” In December 2018, Herdklotz was also quoted in the High Country Press saying, “‘We think this is the direction that the town almost has to grow. The town is going to be moving some of their offices out here, we’ve got the soccer fields right next to where we are, Rocky Knob mountain biking park, we feel great about this side of town. As it grows, we’re happy to be here.’” Listings on AirBnB and Zillow cite their locations in East Boone as a perk. In the latter part of 2019, the name seemed to become more official, partly through the efforts of Harmony Lanes, an advocacy group for multi-modal transportation in Boone. The group proposed the East Boone Connector project to the NC Department of Transportation, which would provide a protected bike and pedestrian path along Bamboo Road from 421 to Wilson Ridge Road. The project was approved by NCDOT, which will pay for the connector as part of future plans to widen the road. The state government’s adoption of this name for the project suggests that though the name East Boone grew out of a marketing campaign, it will become more officially ingrained in the material culture of the area.

East Boone isn’t the first new name given to this area. Hatchet Coffee sits on land that once belonged to the Cherokee, land that was then named after the type of folk hero Americans like to use to make colonization seem adventurous and romantic rather than violent in ways that are still felt hundreds of years later. Human migration, violence, evolution, misunderstanding—any number of factors shape the names we give places or things. As for Hatchet itself, owner Jeremy Parnell said to Sprudge they wanted to choose a name that reflected love for Boone’s natural surroundings, that they “wanted a symbol that would be easily recognizable and relatable to those who also love the outdoors.” The name roots itself in the romanticized outdoor adventure culture of Boone – a culture that sometimes excludes people who don’t have the ideal gear or bodies to participate.

To carry that a step further: consider the geisha versus gesha debate. In her article for Sprudge, Jenn Chen cited potential reasons for the change in name as a simple misspelling, a romanization of a word from Kafa, or a deliberate choice to use a more familiar, exotic word for marketing purposes. Regardless of the origins of the change in spelling, the specialty coffee industry fetishizes this coffee using a name that carries a heavy weight of orientalism and colonialism.

The discovery of East Boone won’t change the world. Not even the world of coffee. The name gave a good laugh to other folks I mentioned it to, who are accustomed to the town vs university vs local dynamics, where anyone whose grandparents didn’t live in the area can never really gain the clout of being a “local.” But what will the discovery of East Boone do to people who were already struggling to afford rent or property taxes?

Hatchet Coffee draws me in for a lot of reasons. Most importantly, their coffee is good, but they do a lot of other things I really admire in shops:

- Creative yet unpretentious menu. So many shops seem a little too try hard with their menus, trying to shoehorn espresso into their take on a perfectly good cocktail or crafting a recipe-blog-length Instagram story about something that is essentially a latte with syrup. Hatchet consistently puts out seasonal menus that offer both classics and surprising new combinations that are delicious and have a sense of fun and whimsy that’s often missing in coffee.

- Excellent service. I once brought home a bag of coffee from Hatchet that I found a pebble in (before dumping it in the grinder, fortunately). When I brought it to their attention, they not only replaced the coffee, they mailed me two other bags (including a Costa Rican gesha), stickers, and a camp mug, along with a personalized note.

- Welcoming space (again, prior to COVID). Plenty of comfortable seats, work tables, and parking make for an easier place to spend time than other shops in the area.

Hatchet has been a completely positive addition to my visits to Boone. But what if I were still living in that trailer park? Would I feel as welcome? Would I be able to afford anything at one of the few businesses within walking distance of my home? At its core, the question here becomes one of what a business owes its neighbors, where its wealth goes, and whether those in possession of capital are the ultimate arbiters of how communities grow and who they include.

In Durham, my second home, we’ve seen this play out in pernicious fashion this past week with East Durham Bake Shop in the news. The owners of the business, who had a successful Kickstarter campaign rooted in assertions of service to the community, have been accused of creating a toxic environment of racism and transphobia for employees. Furthermore, they’ve been accused of policing who is allowed to use their suspended coffee system (where someone can purchase a drink or food for a stranger), asking homeless people to leave if they’re not making purchases (when other non-paying guests are allowed to stay), and targeting Black people with extra surveillance (even going so far as to take special cleaning measures after Black customers vacate their tables.) While their actions are atrocious by any measure, it seems even more egregious when considering that they were among the first white gentrifiers to Columbus the neighborhood and had recently made a show of supporting Bakers Against Racism.

I believe that Hatchet and other East Boone businesses mean to have the community’s best interests at heart, and I don’t expect anything as exceptionally toxic as the East Durham example is happening. But, like me living and working in Durham, they bring their lives and work into a context in Boone they might not be fully understanding, even if like me they love their chosen home the best way they know how. As 2020 challenges us to examine what the future of our communities and businesses look like, I think it’s important to be mindful that good intentions don’t necessarily mean good outcomes. Creating a new community in a new place doesn’t mean you start with a blank slate.

-

Recipes for the great-great-great-grandchildren

My sister is going through boxes of photos and papers and notebooks that my mother wanted to get rid of but did not want to be directly responsible for throwing away. Usually I end up with baby photos of relatives I barely speak to or photos of myself as a teenager that make me realize that someone should really have told me I was pretty, and someday I’ll make someone else throw all that away. But this week’s find was a little more Precious Moments on the surface because she came across recipes handwritten by our Granny Abby.

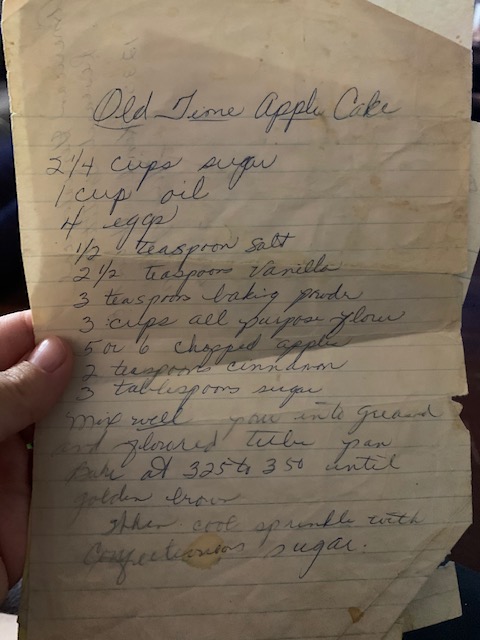

Casey tends to send me photos of things so I can decide whether I want them, and the first one she sent me was a recipe for Old Time Apple Cake. A few things:

If you can read this handwriting, you, too, can have a secret family recipe. The footnotes: (1) I think they settled on 1930 for her death certificate. (2) This is the Granny who had a whole secret family of 4 children that she abandoned prior to meeting my Grandpa. Thanks to 23andMe, Mom meets new family all the time. - We’re hill folk. We grew up near Boone, NC, and Granny grew up in West Virginia. Apple cake is pretty common across the mountains, although a lot of folks may be more familiar with apple stack cake and the dubious folklore of wedding guests each bringing a layer of cake to contribute.

- “Old Time” screams to me that this recipe might be lifted from a church cookbook and meant for revival or homecoming. But it also leaves me wondering what “Old Time” would have meant to Granny and how far back the roots of this recipe go, particularly since she was a notorious liar about many things and no one knew her exact age. The courthouse that held her birth certificate burned down, and Great-Granny Flossie claimed to have forgotten the year of Granny Abby’s birth.1

- Granny was not one of those grannies whose biscuits you dream about but can never replicate. I was seven when she died, so I don’t remember much about her other than the chain smoking that finally took her out. I asked Mom if she baked or cooked and she said, “She did, but not great and not willingly.” I did not expect to ever get a family recipe handed down from a dusty box, least of all from this woman.2

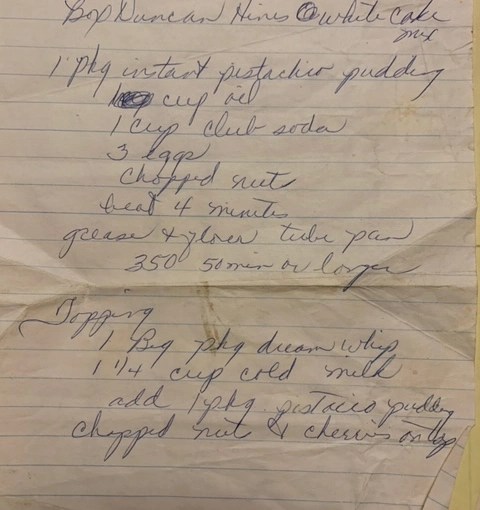

This is a nightmare. It was the second recipe that whispered, yes, child, this is your history: Don’t bother with a brand name or any kind of helpful guidance! Literally just toss a couple of boxes of powder and some soda in there.

It’s also this second recipe that got me thinking about the dusty boxes that someday my grandchildren might sift through. Although she wasn’t much in the kitchen, Granny did come from an era where people had more cooking knowledge. Whereas I had to learn in what order and how to mix ingredients for a cake through baking blogs and working at a cafe, she would have learned that at home from her mother or grandmother.

Millennials (and Zoomers too) have tended towards “cognitive offloading” when it comes to home economics tasks like cooking, relying on the internet for basic instructions. Even though I get creative sometimes in the kitchen, I hardly ever write recipes down. If they are written, they’re online in emails or Google Docs that, given the nature of digital media, could become inaccessible or simply disappear. Whether it’s through a loss of cooking knowledge, changing availability of ingredients due to climate change or other causes, or gaps in documentation or language, those who come after me might not even understand where to begin if they want to cook like Granny.

Take, for example, recipes from the Yale Babylonian Collection. In 2019, scholars attempted to reproduce dishes that were first prepared almost four thousand years ago and were recorded on cuneiform tablets. One such recipe for a vegetarian stew known as Unwinding reads thus:

I’m a mediocre cook. I’m not a scholar immersed in re-creating historical food. So when I first read this recipe my thoughts were:

- How do I prepare the water? Am I boiling it? What kind of pot or pan is it in?

- What kind of fat am I adding? Is it animal fat even though they say meat is not used? Is it an oil? What kind of oil would they have had at the time – olive, maybe?

- What’s kurrat?

- Do I just chop up these ingredients like I would for a soup now?

- By dried sourdough, do they mean sourdough bread? Or something like a dried up starter?

And so on. While some basics of food preparation and the range of what’s acceptable to human tastes might remain the same, there’s a giant gap between what these people knew and what I know about food. There’s also a giant gap in what foods are available. Colonialism and environmental destruction have changed the landscape of foods dramatically over the course of hundreds of years.

Right now, we’re going through another era of incredible change. Stuck inside with COVID-19, a lot of us are cooking more and learning to stock a pantry rather than shop daily for our food needs. The economic depression we’re in threatens to end restaurants and food businesses that have been part of our culture for decades. Climate change may cause the extinction of many plants and animals we rely on for food. And, as mentioned before, we’re hardly writing any of this down in a durable material way. So, what happens if I keep these recipes from Granny in a box and somehow they survive to the beginning of the next century? I think the apple cake one might be “old time” enough in tradition to survive. But here’s what my grandkids might get confused by in the other recipe:

Ingredients

Box Duncan Hines white cake mix Duncan Hines is a Conagra brand, which seems too big to fail, so a record of what this is might at least survive. But considering it’s full of white flour and sugar, consumers making different dietary choices might drive it into extinction and it’d be impossible to find on a shelf in whatever their version of a supermarket looks like. 1 pkg instant pistachio pudding Pistachios are threatened by drought and heat brought by climate change, but a lot of these are based on artificial flavors. Pudding mixes, like cake mixes, seem to be a holdover from another culinary era and might also be difficult to find. 1 cup oil What kind? Canola, olive, coconut? 1 cup club soda It took me some googling to figure out the difference between club soda and other carbonated waters, so I imagine this might also be an unfamiliar ingredient. Also, are we still avoiding the metric system? 3 eggs Eggs seem pretty simple. But who knows? Maybe a new substitute comes from a lab? Maybe it’s not chicken eggs that are common but duck eggs? Chopped nuts What kind? How to chop them? Directions

Beat 4 minutes Is beat still used as a term for mixing? Do they know how to beat eggs? Grease and flour tube pan What to use to grease and flour the pan? It wasn’t mentioned above. What’s a tube pan? [Bake at] 350 [degrees] 50 min or longer I already had to clarify the shorthand used here, so would they be able to fill in the blanks? Are ovens the same? How to know when it’s done? Topping

1 Big pkg dream whip I had to look up what Dream Whip is. It’s already hard to find in stores. What’s the size of the big package? 1 ¼ cup cold milk Same issue as the eggs – there’s potential milk substitutes in the future. Also still using Imperial measurements? Add 1 pkg pistachio pudding Is this the same package mentioned before or do I need to buy another? What am I adding it to? Chopped nuts and cherries on top The cherries came out of nowhere. This is a disaster. Good luck, kids. Granny needs a cigarette.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.